Some of the things I am: blogger; curator; writer; reader; editor; Internet & and print publisher; music lover; phonograph player; radio collector, honourary Canadian; product of experimental education in high school and college; progressive; bicyclist; husband; father; friend; dog-lover; sports enthusiast; breakfast cook; film noir fan.

—

Early Days

I was born in Cleveland, Sept. 22, 1954, right on the cusp of autumn. In my early teens, when I read The Hobbit and then The Lord of Rings trilogy, I identified with the hobbits Bilbo and Frodo Baggins, for much of the action in the books was triggered at their birthday parties, which Tolkien wrote fell on September 22. My arrival that 58 autumns ago coincided with one of the great sporting disappointments in Cleveland history, which I have written about in a blog essay called How to Enjoy Sports Even When Your Teams Have a History of Failure.

Growing up in the hotbed of rock n’ roll that was Cleveland in the 60s and 70s, I started going to hear bands live when I was just thirteen. Music Hall, with its ornate carved fixtures and maroon velvet seats was a regular venue for bills such as Cream with Canned Heat; the Grateful Dead with the New Riders of the Purple Sage; Traffic; John Mayall; the Moody Blues; the Allman Brothers; and The Band. In 1969, a small nightclub called La Cave hosted Neil Young for two consecutive nights, shows my eighteen-year old brother Joel, and I, fifteen at the time, somehow both got into. This was only weeks after the break-up of Buffalo Springfield, and Neil had not yet formed up with Crazy Horse. He played solo and with a backing band called The Natchez Trace. On the second night, we approached Neil–rail-thin in buckskins with trailing fringe and a bit shy–introduced ourselves, and shared an appreciative handshake with him. In my later teenager years, once I was old enough to get in to bars, I discovered a great Cleveland blues musician, Mr. Stress. I followed him avidly for more than a decade. In 2011 in Rust Belt Chic: The Cleveland Anthology I published a personal essay, Remembering Mr. Stress, Live at the Euclid Tavern.

Mendocino County, 1970

The summer before I turned sixteen, Joel and I embarked on a journey from Ohio out to the West Coast in his van. Along the way, on July 4 weekend 1970, our van had brake trouble. We limped into a town, Deadwood, South Dakota, spewing smoke out of our rear axle. Just as we entered town trailing smoke behind us, we heard gunshots, or fireworks, or backfires, we weren’t sure what it was, where it was coming from, or if it was coming from us. We limped in to a gas station where we asked about all the explosions. From the attendant we learned that in Deadwood every July 4 weekend was Wild West days, and this day the notorious local shooting from the 1870s, when Wild Bill Hickock was killed by a card-playing rival–was being reenacted that very hour. At the garage we also learned that we’d be waiting a few days, maybe most of the holiday week, for a new part to come from Detroit.

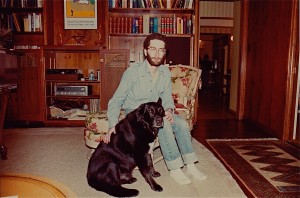

We parked and locked the van, walked to a lake outside of Deadwood, set up a campsite there and marched back into town to do something we had hoped we might have the chance to do during the long trip west–adopt a dog somewhere along the way. We asked locals for directions to the dog pound and one friendly cop took us to the squat cinder block building that was the local pound. “Only one dog in there,” he told us. We agreed to have a look. Entering the building we saw a calm canine in a cage. The black form stirred a little and the cop told us what he knew about “Coach,” a mostly black Lab male. He said that an old potato-creek Johnny, local slang for a throwback gold prospector–Deadwood’s sister town was nearby Lead, SD, home of the only active gold mine in the continental U.S., where local streams ran gray from the cyanide in the mining process–who had lived with this dog in the hills outside of town, raising him from puppyhood. When the old man died, a family in town had gotten in the habit of feeding Coach on their open porch, but had never really adopted him. He slept on their porch, or sometimes rough around town. Almost three weeks earlier, about to move some miles over to the next canyon, the family had brought Coach to the pound. There he had lain for just one day short of three weeks, the limit for a canine transient, after which he was going to be put down.

About halfway through this lengthy chronicle, the dog emerged from his wire home, and lifting a rear leg, began peeing a bulls-eye directly into the drain at the center of the small building’s cement floor. Noticing us watching the dog’s marksmanship and care, the cop said, “Oh, yeah, he’s real clean. Doesn’t like to dirty up his own cage, so we let him out a couple times a day.” That was all we needed to hear, and so we paid the municipality of Deadwood $5 for the right to adopt the dog, whom we quickly renamed “Noah.”

The rest of our western jaunt featured a six-week stay in northern California’s Mendocino County, along the Navarro River on a ribbon of land provided to campers by the Monsanto company. Nowadays known for practicing the dark arts of genetically modifying crops, Monsanto’s more liberal willingness in 1970 to let people camp on their land meant that dozens of freaks and hippies were finding a home amid the redwoods of Mendocino County on land parallel to State Route 128. Joel and I parked our van in the woods about even with a certain mileage marker, 3.28 was ours–and folks referred to these markers to direct others where they could be found. Noah lived in the woods with us, and we made many friends in adjacent campsites. Evenings featured communally cooked food, herbal smoke in the air, and neighbors sitting around campfires reading aloud from The Lord of the Rings. A few months after our stay along the Navarro River, Rolling Stone, still quite a new publication at this point, reported in its “Random Notes” column, that the place to be in the summer of 1970 had been in the woods along the Navarro River. Sadly, by then the scene had already lost its magic, with the county discouraging the arrival of more campers after one died in a drowning incident on an improvised rope swing over the river. Joel and I were real lucky to have been there and experience that special place and time.

A few weeks into our stay along the Navarro River, our dad, Earl, made a plan to fly from Cleveland to San Francisco. Joel was going to sell the van and buy another vehicle in which the two of us and Noah would travel back to Cleveland at the end of the summer. Dad came to help us sell the van and buy another vehicle. Joel and I arrived in the Bay Area a couple days prior to Dad’s arrival, and one night we were able to attend a Grateful Dead concert in Berkeley. It was a great show. A few days later, after Earl arrived, we found a buyer for Joel’s van. He turned out to be an undercover cop, a narc, who lived in the Bay Area. Joel and I did a mild double-take when he told us what he did for a living and then mentioned that he had worked the Dead concert where we had been a few nights earlier! With the van sold and a used pick-up truck purchased, Earl flew back to Cleveland. A week or two later, with the end of summer vacation and Labor Day looming, we drove back across the country. I rode in the pick-up bed much of the way, laying there with Noah and another big dog, Farkel, the pet of two friends up front with Joel. We arrived back in Cleveland just a couple days before school was supposed to start for my tenth grade year.

Friends School/The School on Magnolia

When school did begin, following on what had been the profound events of the summer, I discovered I had little to say to my peers, and felt deeply alienated at Shaker Heights High School. Within a few weeks I told my parents that I wanted to drop out of the public school. All I really wanted to do, I said, was go on long walks with Noah all around the leafy suburbs of Cleveland and read long novels by writers like Thomas Mann and Fyodor Dosteovsky. I couldn’t relate to anything else. Mom and Dad were concerned, as were my two older siblings, but ultimately it was agreed I would do what I wanted to do. Long walks and long books ensued. In January ’71 I enrolled at an alternative high school that had been opened in 1969, first known as Friends School (and after it didn’t formally affiliate with the Quakers), the School on Magnolia. It was a great place for me, with 50-60 students, some great teachers and a style of self-governance that was modeled on Quaker practice. Our weekly town hall began with silence and we operated under consensus as our guiding governing principle.

Though missing about three months of school following my early exit from Shaker Heights HS, I didn’t miss a beat and managed to graduate from the School on Magnolia the same month, June 1972, as my former high school classmates. I got a first-rate HS education, with deep dives into evolution, literature, creative writing, and learned how an experimental institution may govern itself. I also relished the free time I had to walk with Noah and read whatever I wanted.

Franconia College

From the School of Magnolia it was a natural leap to discovering and then enrolling at Franconia College, located in the scenic village of Franconia, New Hampshire, in the White Mountains. This was an also an experimental, self-governing school. It had been started in the early 60s, as Dow Academy, a two-year school, and then became a four-year college in the late 60s. In the fall of ’73, my first term, I served on the committee that reviewed faculty contracts, a frothing cauldron of controversy and campus politics (there was no tenure, so teachers had 3-year contracts that came up for renewal or non-renewal). In parts of my second and third years I was the moderator of our weekly community meeting, where students, faculty, and administrators were often confronted with thorny issues, such as the College’s financial difficulties. As in high school, at Franconia I also became very involved in school governance.

In October 1977, at the end of my junior year, Muhammad Ali was the a recipient of the first Franconia External Degree (a FRED) and traveled up from New Haven, CT, to be a guest of the college at a commencement where he accepted his diploma. FRED was a special degree program we’d started that recognized people for significant life experience outside of formal education. Upon admission, new FRED students were granted a two-year Associates Degree, which then gave them a chance to complete a BA in only two more years. I gave an address the afternoon Ali visited our campus. Being on the same dais as him was amazingly awesome. I also met him beforehand, a memorable moment I have written about here on this blog.

Like the School on Magnolia, Franconia College was an avowedly experimental institution. Importantly, we had 2 student trustees as members on the Board of Trustees, along with the 2 faculty, 2 administrators, and 2 civilians who sat on the body. I was a student trustee my fourth year. Franconia never had more than 400 students–there were never enough students paying tuition, leading to frequent budget shortfalls. I was graduated in June ’77, but remained a trustee into what was supposed to be the next academic year. During the fall of ’77, the Board was far along in formally aligning the College with a fledgling program, Elderhostel, not yet a household name in continuing/adult education. Elderhostel had begun in New Hampshire. Like FRED, the new initiative was designed so older students–with more life experience and different backgrounds than our typically early 20-something students–could have access to degrees in higher education. We also relished the opportunity to place students in their 40s, 50s, 60s, even 70s, with those in their 20s–in shared classes and on campus together, year round if possible. This would have been a true union of the Sixties’ promise of experimental education coupled with lunch-bucket commonsense equal opportunity.

In hopes of implementing this new affiliation, College staff had written a grant and applied to the Carter Administration’s Dept. of Aging for funding. This federal agency, part of cabinet department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW)–later dismantled during the Reagan administration ederal , since abolished. Fortunately, we’d received verbal assurance from officials that they wanted to fund it, and the hope was that in the early days of ’78 we’d get our grant, with money from D.C. soon to flow thereafter. Alas, it was not to be. The Manchester Union-Leader, whose arch-conservative publisher William Loeb had always despised the ‘hippie college in the White Mts.’ printed a false story about the grant. It was during the long winter break at the beginning of 1978. The Franconia campus was empty as classes wouldn’t resume until late January, and I was back at my family home in Cleveland. In December, our enrollment, always low, was even lower than usual, below 200 students, but we believed the infusion of new students in the coming spring was going to insure our future. However, the same newspaper that had torpedoed Edmund Muskie’s presidential candidacy in 1972 somehow reported that our grant was a ruse to fund a sham program, that it would go right into our regular operations. (We never did learn how the newspaper even learned about our grant application; somewhat wiser now in the ways of Washington, I suspect there was a Republican holdover from the Nixon or Ford administration who shared Loeb’s resentment of the College.) The story painted a dark picture of a scheme that would divert money into the College’s general fund, with no noble program being mounted. The Carter administration backed away, the grant died, and the college never reopened for its next term.

Owing to Franconia College’s perennially parlous state, we might have folded later anyhow, but I’ve always believed that the Elderhostel connection would have allowed the College to reach some level of financial stability. Seeing a recent OWS video from Littleton, NH, about the lack of education opportunity in the remote North Country, it saddens me to think how Franconia College could have really become an educational linchpin in the region.

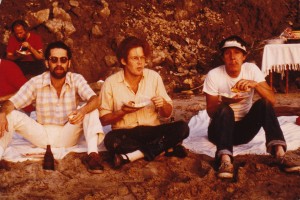

At Franconia, I studied biblical criticism and the history of religiosity (with a teacher to whom I became very close for a time, William Congdon); literature (delved deeply in to the Faust legends in one course and wrote a paper on Faust that I still have, with a professor, Donald Sheehan (who also taught Greek) and the Canterbury Tales with teacher David Ackley, for whom I wrote about “The Nun’s Priest’s Tale” ; and the philosophy of education, complemented by my participation in the self-governance mentioned above. I had several many teachers and made close friends, two in particular, Robert Henry Adams (later a rare books, prints, and painting dealer) and Karl Petrovich (a talented fiddler and devoted student of traditional music), both pictured with me below in the mid-1970s. Sadly, both Rob and Karl are now gone–they died within a few months of each other, in November 2001 and January 2002.

At the left, I’m enjoying a picnic on the shores of Lake Michigan with Rob Adams and Karl Petrovich, circa 1970s.

I lived with Noah in a tiny cabin on a dirt road outside of the village, very near the house where Robert Frost had lived in the second decade of the twentieth century. During my last year in the cabin, the Frost house became a museum and poetry study center My tiny cabin had a great view of the Franconia Range, especially Mt. Lafayette, with its rocky top and snowy flanks.

The summer after graduating I gave up my cabin in the mountains and moved back to Cleveland, at least for a while, I thought at the time. Karl was planning to stay in the North Country, while Rob also moved back to the midwest, Chicago, his case where he began his business. known as Robert Henry Adams Fine Arts. That summer I was a vendor at Cleveland’s Municipal Stadium, selling beer at Cleveland Indians’ baseball games. I worked about 50 games (out of a possible 81 in a home season), and loved it. I was just about the only kid from the eastern suburbs (meaning not a person of color or ethnic minority) in the vendor corps. I enjoyed walking the wide open grandstands, calling out such pitches as “Beer Here!” and “Get Your Cold Ones!” The job was good all summer, until the night of the first Cleveland Browns exhibition football game. I had been on the fence about even working the game, and was I right to have been wary. The football crowd was an unruly, inebriated mass, and I was lucky I didn’t have my rack of beers stolen along with all my earnings. I stopped vending then.

Though back in the Midwest, the lure of the North Country was still strong, and with Karl clearing land for a house he was going to build on Wallace Hill Road, above Franconia, Rob and I re-joined Karl and his wife Hope Requardt to help them build their family home. When I arrived in September the foundation had been dug, but no other work had begun. Karl hired a well-drilling company for his rocky hilly lot and not until 600 feet later did they finally find a reliable water supply. While the heavy steel pistons drove in to the earth barely a hundred feet away from the building site, we put up the house. I became a somewhat useful homebuilder, with roofing proving to be my best talent. We framed it all in September and October, enjoying a long autumn and the healthy outdoor work, living very rough in soiled flannels and denims. I stayed nights at the home of the philosophy professor, Bill Congdon; along with his wife and sons they all made me welcome. As the cold and wet of fall became winter, and with Karl and family roofed in, I drove back to Cleveland, reunited with Noah and planned to embark on a job or career search.

Undercover Books

While finishing my last year at Franconia, I had hoped that I might find a professional niche for myself promoting ecumenical dialogue among Jews and Gentiles, maybe working for an organization like the Anti-Defamation League, combating bigotry, anti-semitism, injustice, and intolerance in some fashion or other. After returning to Cleveland, I got serious about looking in this direction, and quickly found that without an advanced degree, like a Masters, I was going to get nowhere in the field of communal service. But I was a refugee from traditional education, a veteran of experimental education, and grad school was the last thing I wanted to do.

Before I could become too disheartened about this fact I started focusing on a plan that my sister and brother had been hatching while I was still back in Franconia working on Karl and Hope’s house. Pam, the eldest of us three siblings, had worked in Cleveland department stores, while Joel, the middle sibling, had worked for Kay’s Bookstore, in downtown Cleveland. Now, they wanted to open a bookstore in our home suburb of Shaker Heights–which had never a bookstore within its city limits–and were also enlisting our parents, Earl and Sylvia, in the idea. I signed on too, for what I thought might be only a short stint, while I sized up my post-Franconia opportunities. As I’ve written in an earlier post, May 4–Always an Eventful Date, we opened Undercover Books on that date, in 1978. We eventually operated three branches of Undercover Books. The bookstores gave us three siblings a veritable education in the book business. I ended up working in the bookstore with the family until 1985, when I moved to New York and within a year began working in publishing. If you’d like to pick up the story from here, I suggest you read about the next chapter of my career in the counterpart page to this one, PT–Professional. Please note I am also developing a page called PT–Photos, with many images that will complement those two pages of professional and personal history.

Two favorite quotations

“If the rich could hire other people to die for them, the poor could make a comfortable living.” A Yiddish proverb quoted by W.H. Auden in his commonplace book A Certain World

“It’s hard to soar like an eagle when you’re on the ground with the turkeys.”–Seen above the bar at Cleveland’s Euclid Tavern, circa 1970s-80s, source unknown

Three of my own coinage:

Being an editor allows me to express my latent religiosity, since I spend so much time praying for my books.

Publishing companies have long been known as ‘houses’ because they (are supposed to) offer hospitality to writers.

Stay neutral, lean positive.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!